Social work

and democracy

From an understanding of democracy that places equal opportunities for participation in the foreground, this pressure has a counterproductive effect.

However, the dilemma cannot be completely resolved and must be considered and evaluated on a case-by-case basis. The problem can only be briefly touched upon here. However, it is important for social and youth workers to be aware of the possible dilemmas.

Notwithstanding the political conditions indicated above, it must be stressed that those who perform social work on a daily basis also have many opportunities to shape democratic attitudes in the recipients of their work.

Often, the sensitivity with which they approach these recipients to different social, cultural, physical, etc. characteristics will determine how they influence the future behaviour of these people. It also influences whether those on welfare will later find it easier to maintain a link with the democratic system, or whether they will continue to lose faith in it and be more likely to adopt radical or even extremist attitudes.

In this sense, social workers' interpersonal competences and democratic awareness may also determine the future behaviour of the people they meet in their professional capacity. For this reason, this handbook focuses on the development of such competences and awareness.

After the Second World War and in the course of the expansion of welfare states, the role and self-image of social work changed.

With the emergence of a critical civil society in the 1960s and 1970s, the question arose as to whether social work should be understood as an instrument of control by the state or as a critical and emancipatory profession. Participation, empowerment and critical thinking become new principles of a progressive understanding and self-description. Social work now increasingly saw itself as a profession that supports human rights and social justice. This is also reflected in official documents such as the declaration of the International Federation of Social Work from 2014, which formulates a global definition of the Social Work Profession: “Social Work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people.

Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work” (IFSW 2014). Democracy is not explicitly mentioned here.

This has to do with the complicated relationship between social work and the institutions of representative democracy. In an official statement from 2016, the International Federation of Social Work commits itself to an active role in “building real democracy”: “IFSW promotes the development of legislation in all countries that recognizes the importance of community involvement in building real democratic structures.” (IFSW 2016) The statement also points out that democracy should not be reduced to elections. The mission statement of the European Association of Schools of Social Work refers to similar values: “In fulfilling its mission, the EASSW adheres to all United Nations’ Declarations and Conventions on human rights, recognizing that respect for the inalienable rights of the individual is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace. Members of EASSW are united in their obligation to the continued pursuit of social justice and social development.” (EASSW Website 2021)

In France, social work has developed according to several separate genealogies (social service, specialised education, animation), each lineage having its own axes of cleavage and historical traditions.

Social workers are present in a wide variety of institutions: social centres, early childhood services, institutions for the disabled and elderly, etc. (Autès, 1999). They are employed by state and local authorities, but may also belong to associations. What brings together such varied missions, practices and actors is undoubtedly their aid or service relationship.

However, social work in the country faces a number of challenges, namely social workers’ loss of sense of purpose while being trapped in segmented and accounting logics and being stuck between systems and professionals who no longer know how to take into account their overall situation. It is only an indication of a wider problem boiling down to a lack of coordination of social policies in the country. In order to respond to these challenges, an inter-ministerial Action Plan for social work and social training has recently been adopted in the country, although its results have yet to be seen.

Social work in Poland has come a long way – from institutions established after the First World War based on European standards referring to the idea of "democratic upbringing", through the abandonment of these principles during the communist period to the construction of a new system in the 1990s after the political transformation in the country. Nowadays, the vast majority of social work in Poland is performed within public welfare institutions and faces significant challenges. The role of most of its functionaries is still reduced to the distribution of public allowances or material help and the completion of other bureaucratic tasks. Social workers, although often very competent and aware of the deficiencies of the system, have little space and time for performing their functions properly (Kozak 2012a). They are overburdened with tasks – each year an average Polish social worker works with 105 individuals from 45 families (NIK 2019). They also deal with inadequate working conditions (such as lack of space for individual meetings with clients) and insufficient salaries. The Polish social assistance system can be described as an emergency welfare state – it is concentrated more on reacting to problems than on preventing them. Polish social work within the official system is based mainly on the method of individual case work. Other methods, like group work or community work, are virtually non-existent (for more information see: Kobylińska, Pazderski 2021).

The Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC)

As it was already mentioned above, the most important challenges democracies are facing around the continent and beyond have been recognised by European institutions. In the annual report of the Council of Europe in 2016, then-Secretary General Jagland highlighted the importance of democratic and human rights education for the challenges of today’s societies: “Democratic citizenship and human rights are […] increasingly important in addressing discrimination, prejudice and intolerance, and thus preventing and combating violent extremism and radicalisation in a sustainable and proactive way” (Secretary General Thorbjorn Jagland in his annual report Council of Europe 2016). Based on this conviction, in 2017, the Council of Europe launched the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture, which since then has become the flagship project of educational policies within the Council (learn more at https://www.coe.int/en/web/reference-framework-of-competences-for-democratic-culture).

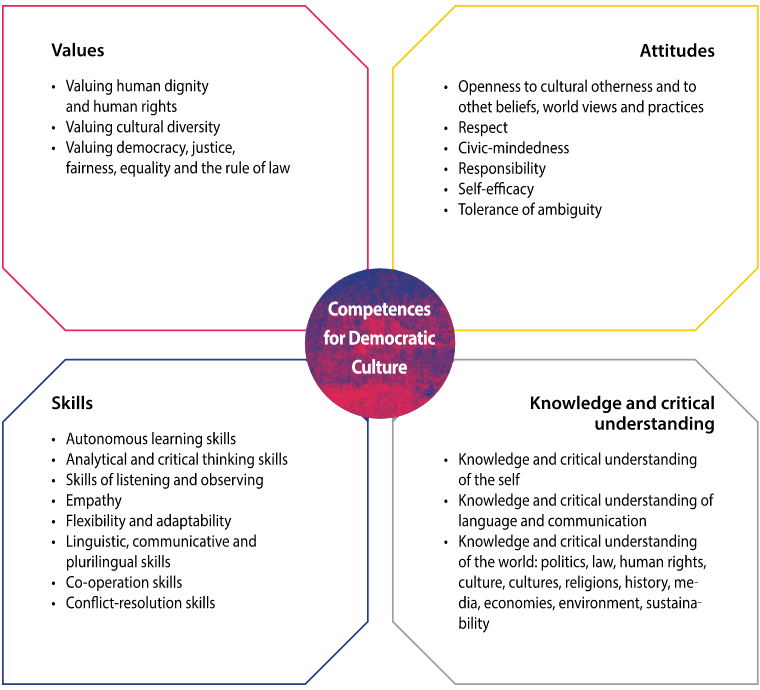

Graph 1: Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture

In this model, essential dimensions of democratic culture are broken down into competences and descriptors. They systematise citizenship education and show that it is not only about knowledge, but mainly about competences. Values, attitudes, knowledge, critical understanding and skills of citizens should be strengthened. This “butterfly” model was initially developed for the more formal setting in the school context. There, it is already being applied, tested and further developed. However, it undoubtedly also provides a suitable framework for less formal educational processes in social and youth work.

This is demonstrated in the documentation of the first pilot projects carried out in the framework of a respective focus group on the Reference Framework established within Network of European Civic Educators, NECE (see: https://www.nece.eu/about-nece/focus-groups/). More information on the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture and its applicability in the practice of educational activities in the non-formal sector can be found in Hladschik et al. 2020. Further methods and material can also be found on the website of expert Rebecca Welge (https://rmwelge.ch/en/about/rebecca-welge).

Check our Partners

Social work, and with it youth work, has a long tradition in Europe but has developed differently in different countries. In relation to the forms of government and questions of power, there are several approaches. Social work is considered first and foremost as a helping profession that supports individuals to cope with their lives. It can also see its role as maintaining a certain social order and trying to guide people into the social mainstream, which is often prioritised by the state. Especially, but not only, in anti-democratic regimes, this tendency promotes the danger of a politically unreflective affirmative attitude towards those in power and towards social inequality.

A modern understanding of social work, on the other hand, is closely linked to democratic goals. Here, the focus lies on strengthening human rights, democracy and individual maturity. Clients, especially young people, are to be empowered and supported on their way to becoming free, competent, but also solidary citizens. This goal may well clash with the goals of the government principals from time to time. For example, the state can commission social work to integrate unemployed people into the labour market. In the theoretical debates on the role of social work, this is discussed as the double mandate and the triple mandate of social work (Staub-Bernasconi 2007). The double mandate refers to the fact that on the one hand, social workers have an obligation to their client (the state), but at the same time, they also have an obligation to the client (the individual) and their well-being. The third mandate is the obligation to fulfill scientific and ethical requirements.This also raises the question of whether social work as a profession should be an actor in the political debate, for example, to advance social and human rights policies.